Remarks prepared for Bruegel online event on “The need for market-based finance after COVID-19″ [check against delivery]

Introduction

Good afternoon. I am very pleased to join this Bruegel event today.

The COVID-19 pandemic – and the necessary public health measures taken to contain it – have rippled through the global economy and financial markets in recent months. The resulting shock – although not originating from the financial system – represents the greatest challenge for the financial system since the global financial crisis more than a decade ago.

We entered this period of extreme uncertainty with the core of the financial system in a better position to absorb, rather than amplify, shocks. Over the past decade, the resilience of banks has strengthened considerably. On the back of post-crisis regulatory reforms, including the introduction and operationalisation of macroprudential frameworks, banks have higher levels of capital, a better quality of capital and more stable sources of funding. As a result, banks are in a better position to support households and businesses through – and out of – this difficult time.

But we also entered this period of uncertainty with a financial system that looks different to what it did before the financial crisis. In recent years, the banking system has seen a gradual decline in its share of total financial intermediation globally. This has been accompanied by an equivalent increase in the share of financial intermediation accounted for by parts of the non-bank financial system, or market-based finance.1

So, in my remarks this afternoon, I would like to focus on the implications of the changing nature of the financial system, with a particular focus on the growth in market-based finance. The financial dislocations observed at the onset of the COVID-19 shock have raised important questions around the extent to which the collective behaviour of parts of the market-based finance sector contributed to the magnitude of these stresses and, by implication, the magnitude of the policy response that was required by authorities to mitigate the effects on the economy. In addition to the immediate crisis response to COVID-19, it is essential that we consider the broader lessons that this episode provides around the resilience of the market-based finance sector from a macroprudential perspective.

The evolving nature of finance

First, let me begin with some headline numbers to give you a sense of the scale and recent growth of market-based finance.

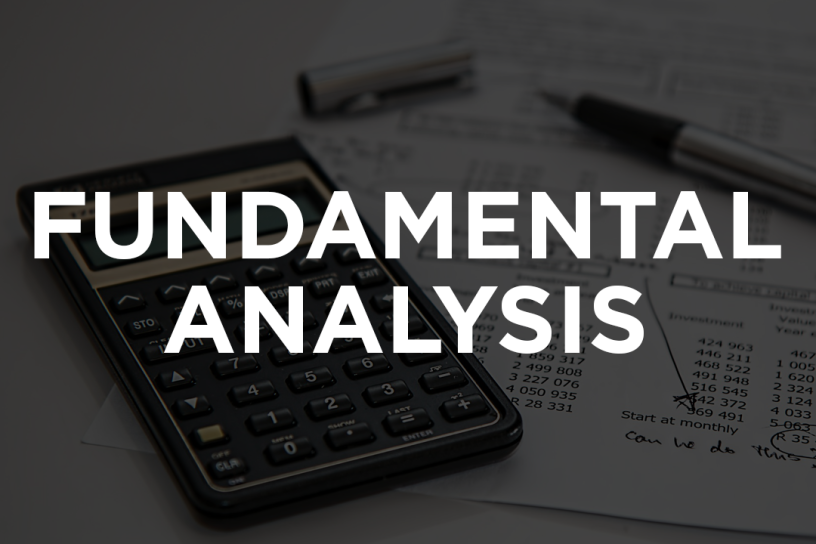

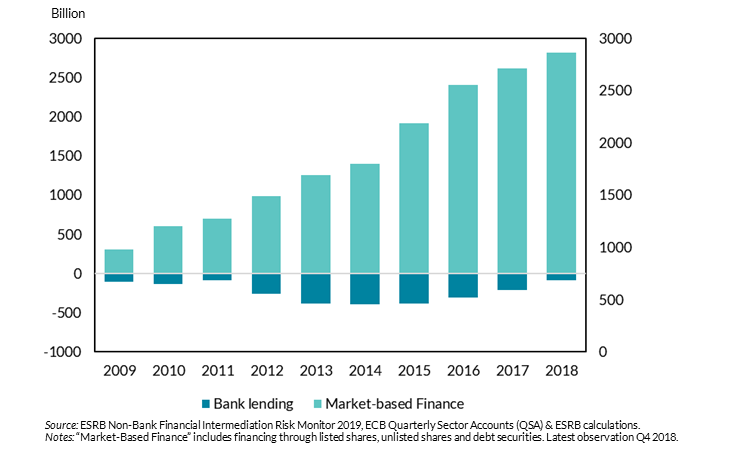

Since the global financial crisis, the world’s market-based finance sector has more than doubled in size (Figure 1: Comparative growth of market-based finance sector (2009-2018)). At a euro area level, the growth has been somewhat slower. Still, non-bank financial institutions now account for approximately 40 per cent of total assets of the overall euro area financial sector.2

These structural developments have been at the forefront of our own work agenda in Ireland in recent years.3

Ireland hosts a large and internationally-oriented market-based finance sector which – similar to global trends – has grown rapidly in recent years. A key contributor to that growth has been the rapid increase in assets under management by different types of investment funds, from hedge funds to fixed income funds. While part of this growth in assets under management has been due to valuation changes, it also reflects cumulative flows of savings intermediated by investment funds.

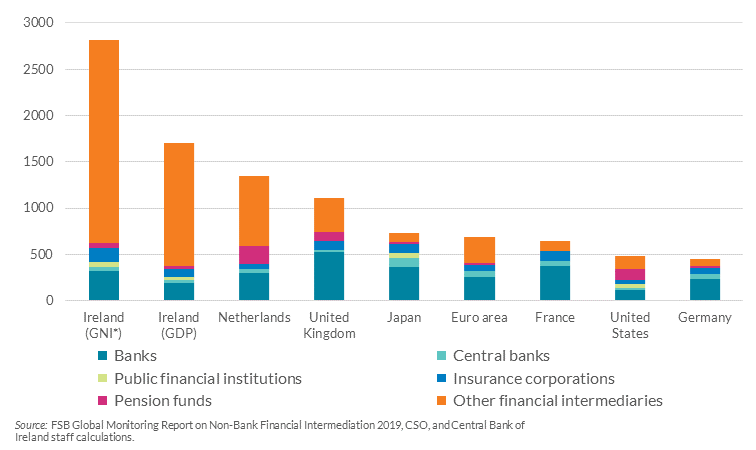

The Irish-resident market-based finance sector is one of the largest globally relative to the size of the domestic economy (Figure 2: Financial assets by institutions type as a multiple of the country’s GDP (GNI*) in 2018 selected countries). Total assets of the sector amounted to over €4.5 trillion in the first quarter of 2020. The sector in Ireland is dominated by investment funds and money market funds, which together account for roughly two-thirds of total assets.

Market-based finance – in Ireland, in Europe and around the world – matters for two reasons. First, because it provides financing to other parts of the financial system. For example, money market funds provide short-term funding to the global banking system, while investment funds hold longer-term bonds and equities issued by other financial institutions. Second, because it provides financing directly to the real economy. Indeed, after the global financial crisis, an increasing share of euro area non-financial corporation funding has been sourced from market-based sources (Figure 3: Cumulative net bank and market-based financing of euro area non-financial corporations, € billions, 2009-2018). The exposures of the Irish-resident market-based finance sector to the domestic economy remain limited but have also been growing, especially via links to the domestic commercial real estate market. In addition, the Irish-resident market-based finance sector provides direct financing to the real economies of a number of jurisdictions, highlighting the cross-border dimension of this form of finance and of course the growing integration of the world’s economic activity.4

So, overall, as the market-based finance sector has grown in recent years, the importance of this form of financial intermediation for the economy and the financial system has also increased. Compared to a decade ago, potential disruptions in the provision of market-based finance are likely to have a more material macro-financial impact.

In that context, at the Central Bank of Ireland, we have been at the forefront of international efforts to close data gaps and to facilitate a better understanding of the flows and interconnections of the sector. These initiatives have put us in a better position undertaken our own risk assessments and to contribute to international exercises that monitor the build-up of vulnerabilities at a global and European level. As the central bank, securities regulator and macroprudential authority, we have also been heavily engaged in policy initiatives, both from a financial stability perspective and to ensure investors remain adequately protected.

The benefits of building resilient capital markets

Market-based finance provides a valuable alternative to bank financing and can facilitate risk sharing across the financial system. In doing so, it can support economic activity both in good times and in bad. Deeper and more developed capital markets can facilitate long-term investment, by allowing businesses to access a wider range of funding sources. They can also lead to a greater choice amongst savers and investors.

Greater diversification in the channels of financing for businesses and households can be particularly important in the face of adverse shocks. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that economies that rely more on market-based finance experience stronger and more durable recoveries from economic crises than those that rely more on bank-based finance.5, 6

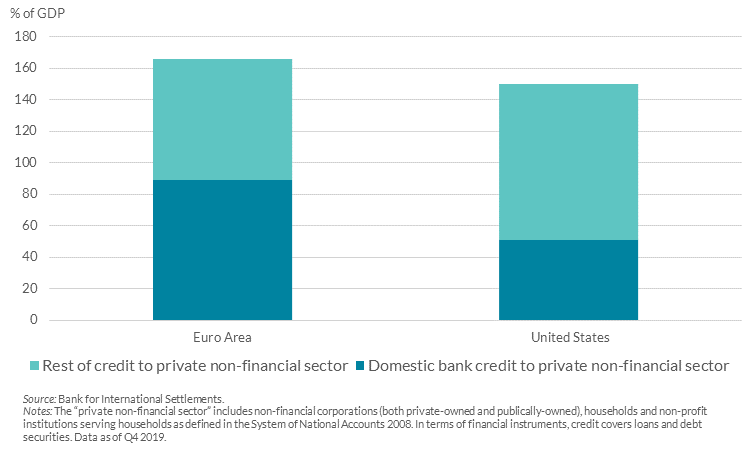

This is why the European Commission has been working to develop a more diversified financial system in Europe through its Capital Markets Union action plan. The supply of finance in Europe is still primarily bank-based. In the euro area, more than half of total credit to the private, non-financial sector is provided by banks. In the US, the equivalent share is closer to a third (Figure 4: Credit to the private non-financial sector as a share of GDP, Q4 2019).7 So continued progress towards deepening capital markets in Europe is important and not just for the development of our financial system. In my view it would also improve the effectiveness of the EU’s overarching macroeconomic policy framework.

Of course, the efforts to develop capital markets need to be accompanied by policies to deliver resilient capital markets. Ones that can provide the benefits of increasing flows of market-based finance to the economy in good times, but which also prove resilient in bad times.

To promote financial stability, we must ensure that the level of resilience in market-based finance is commensurate with its contribution to systemic risk and how it interacts with the financial system and the economy as a whole. Building resilience in market-based finance will ensure that the wider financial system is better placed to absorb, rather than amplify, financial shocks in times of stress.

Structural vulnerabilities in market-based finance

Like all forms of financial intermediation, market-based finance can contribute to a build-up of financial vulnerabilities. Because of the size, complexity, diversity and the very large number of entities making up the global market-based finance sector, financial policymakers scanning the horizon for risks and vulnerabilities face a foggier terrain.

History can be a useful compass to help guide us through the fog. If you look at previous episodes of financial stress, two key sources of financial vulnerabilities appear time and time again. The first is excessive leverage. The second is excessive liquidity transformation. And, when shocks hit, they can transmit through interconnectedness between different segments of the financial system.

Some of these underlying vulnerabilities are also present in parts of the market-based finance sector and have been the focus of increased scrutiny in recent years. I will illustrate these with reference to the funds sector, given the rapid growth in this part of the financial system over the past decade (Figure 5: Structural vulnerabilities in the market-based finance sector can amplify shocks).

Let me start with liquidity mismatches. These can be present when open-ended funds are invested in less liquid assets, while allowing their investors the opportunity to redeem their shares at a higher frequency. Such funds can become susceptible to the risk of large redemption requests in times of stress. Funds with significant mismatches may have to sell assets quickly to fulfil redemptions. In turn, this may lead to a fire sale of assets and a withdrawal of funding from important sectors (for example, banks), which can impair the functioning of key markets and, ultimately, the potential flow of credit to the economy.

Excessive leverage in funds can also be a source of vulnerability in periods of stress. When asset prices fall, investment funds may either seek to keep their leverage at a target level by selling assets, or be forced to do so by creditors. Again, this may lead to fire sales of assets and a withdrawal of funding from other systemically important sectors (e.g. banks), impairing the functioning of key markets. Indeed, leverage can also amplify liquidity risks. For example, funds with high levels of leverage through derivatives may be more susceptible to margin calls in times of stress, putting pressure on their liquidity position.

At the core of these vulnerabilities is the potential for ‘fire-sale externalities’. Actions that individual actors in the financial system might take in times of stress, which are perfectly rational from their own individual perspective, but can also have adverse implications for the markets in which they invest and the broader functioning of financial markets. Fire-sales can have broader market impacts and, in doing so, also influence the behaviour of other investors that are sensitive to price movements. Such dynamics can increase procyclicality within the financial system.

Finally, interconnections abound in the market-based finance sector. Many of these interconnections take place on a cross-border basis. As I mentioned earlier, funds provide financing to other parts of the financial sector. Some unit-linked insurance products invest directly in investment funds. Investment funds and insurers hold shares in money market funds for liquidity management purposes. Funds – for example those that invest in commercial real estate – borrow directly from banks. There are interconnections between different parts of the financial system through derivatives. And, of course, there are potential spillover channels through common asset exposures of investment funds, insurers, pension funds and banks. This means that shocks to parts of the market-based finance sector can transmit to other parts of the financial system and, ultimately, the real economy.

Initial reflections from COVID-19

A number of financial stability authorities have identified these vulnerabilities, particularly in recent years, and a number of policy initiatives have been undertaken – or are in train – to seek to mitigate these.8 So how did the market-based sector fare at the onset of the COVID-19 shock?

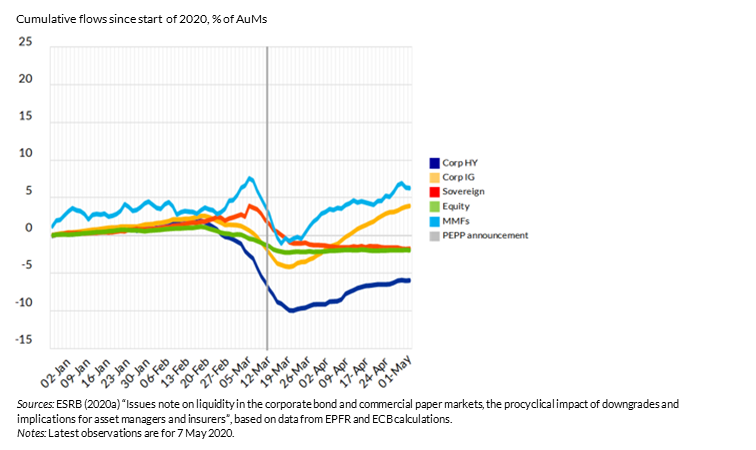

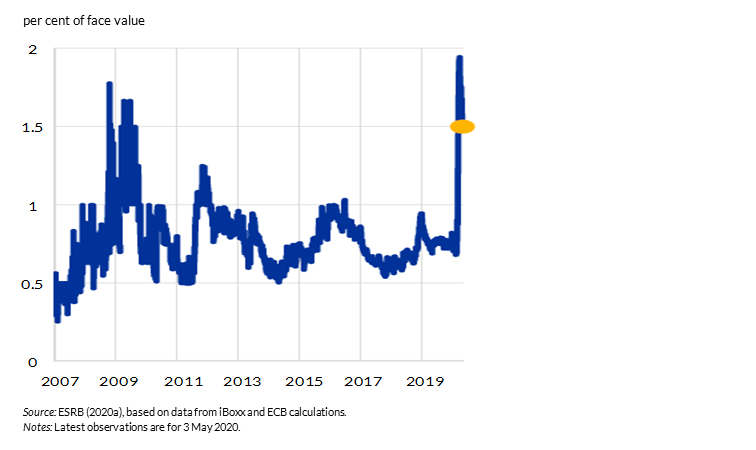

As financial market turbulence, a broader ‘flight to safety’ and a heightened demand for cash swept through a range of markets at the onset of the shock, the fund sector experienced a sharp increase in redemptions (Figure 6: Net flows for euro area domiciled funds).9 Outflows were particularly acute in funds invested in corporate bonds. In the case of euro area high-yield bond funds, for example, outflows as a percentage of total assets under management were the highest since the global financial crisis. The onset of the shock also saw a significant deterioration in corporate bond market liquidity. Bid-ask spreads in the high-yield segment of the euro-denominated market during March and April rose to levels above those seen during the financial crisis (Figure 7: Bid-ask spreads in euro-denominated high-yield NFC market).

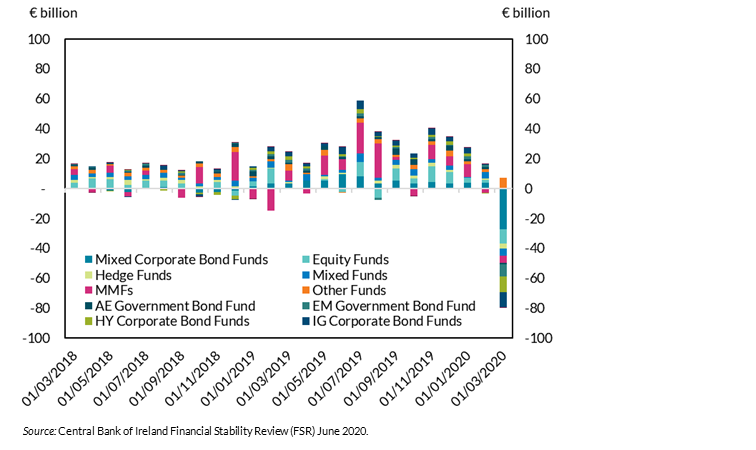

Our latest Financial Stability Review published two weeks ago included an analysis on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Irish funds sector in March and it shows a similar pattern.10 In aggregate, there were around €72bn of net redemptions from Irish-resident funds in March (Figure 8: Flows in Irish-resident funds, € volumes, March 2018- March 2020).

Our latest Financial Stability Review published two weeks ago included an analysis on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Irish funds sector in March and it shows a similar pattern.10 In aggregate, there were around €72bn of net redemptions from Irish-resident funds in March (Figure 8: Flows in Irish-resident funds, € volumes, March 2018- March 2020).

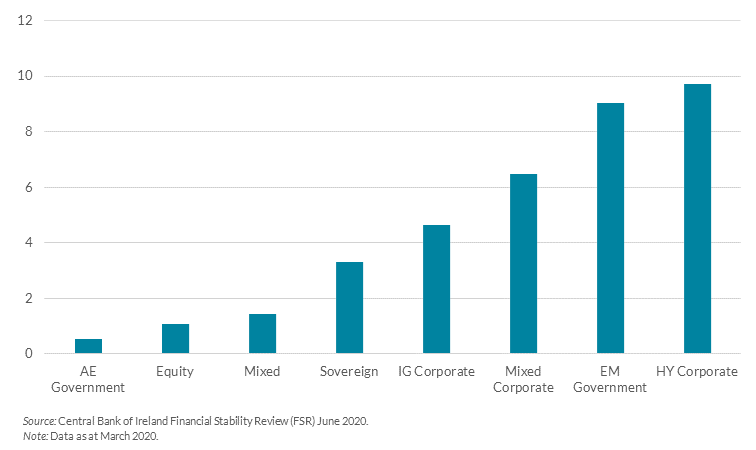

The pattern of redemptions across different fund segments suggests that funds with exposures to less liquid assets, or assets that became temporarily illiquid, were particularly susceptible to outflows. As a share of assets under management, redemptions were highest among corporate bond funds (especially less liquid, high-yield corporate bonds) and EME government bond funds, and lowest for funds with exposures to more liquid instruments, such as developed market government bonds and equities (Figure 9: Outflows in Irish-resident investment funds as a % of previous period’s AUM)).

It is also noteworthy that redemptions from funds were not necessarily correlated with asset returns. For instance, equity price falls were much larger than falls in corporate bond or EME government bond prices. Nevertheless, as a share of assets under management, equity funds experienced much smaller redemptions compared to corporate bond or EME government bond funds. This overall pattern of redemptions would be consistent with the presence of ‘first-mover advantage’ dynamics amplifying redemption pressures in some cases.11

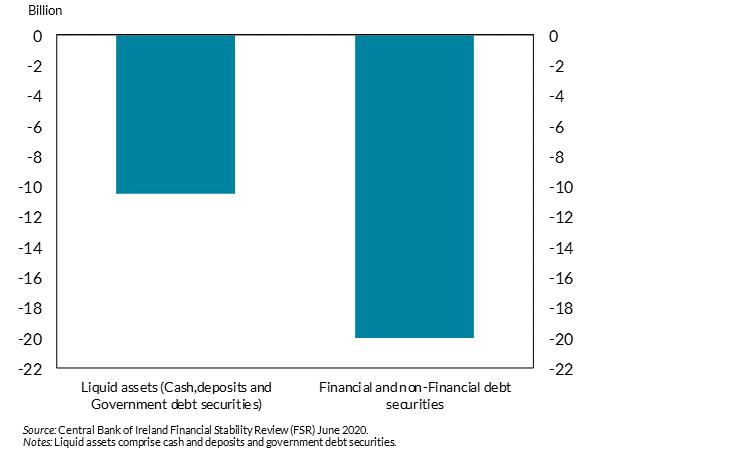

In response to both an increase in redemptions and a deterioration in market liquidity, some funds responded by selling either liquid assets or less liquid assets (such as corporate debt securities) (Figure 10: Irish-resident corporate bond fund asset sales, Q1 2020, € billions). Such asset sales, especially of less liquid assets over a short period of time, may have contributed to further asset price pressures.

Flows out of corporate bond funds have stabilised and even reversed recently, as global central bank interventions have supported financial market functioning. In the euro area, the ECB acted to restore liquidity in key market segments through a number of actions including through expanded corporate and sovereign bond purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) and the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP).12 And tensions in unsecured money markets also eased after the announcement of the pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations (PELTROs), which act as a backstop to market funding needs.13

However, as my colleague on the Governing Council, Vice-President Luis de Guindos, outlined in a recent speech, the liquidity stress we observed in recent months highlights weaknesses in the existing policy framework for non-banks. The patterns that we observed in March suggest that liquidity mismatches in the global funds sector may have contributed to broader financial market pressures.14

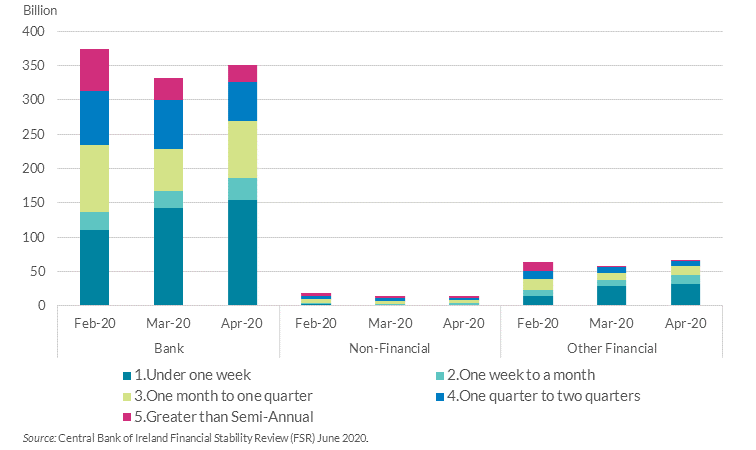

Beyond corporate bond funds, money market funds were another segment of the funds sector that was impacted at the onset of COVID-19. Money market funds are typically used by investors, such as non-financial corporates, for cash management purposes and are, in turn, active players in short-term funding markets. Money market funds globally – including those in Ireland – also experienced a substantial increase in redemptions. For example, US dollar denominated Irish-resident money market funds with investments in private sector debt experienced large outflows in March. These patterns were accompanied by a dislocation in the commercial paper markets in which money market funds invest and spikes in short-term bank funding costs, such as the LIBOR-OIS spread.15 Irish resident money market funds responded to this period of stress by increasing the liquidity of their portfolios and reducing the maturity of their assets (Figure 11: Irish-resident LVNAV MMFs assets by residual maturity, Feb-April 2020, € billions). While this means that money market funds are better placed to meet any future redemption pressures, it also implies that money market funds have only been willing to provide very short-term funding to the banking system.

At the peak of the financial market stress in March, turbulence spilled over to some of the deepest and most liquid government bond markets. Analysis by the BIS pointed to evidence of forced selling by hedge funds and other highly-leveraged funds contributing to dislocations in the US Treasury market.16 The sharp increase in asset price volatility led to an increase in margin calls, in turn forcing funds to sell US Treasuries to generate cash. Leverage acted as an amplifying factor.

Overall, the market stresses experienced in March, together with the unprecedented scale and speed of central bank intervention required to manage those stresses, have brought to the fore previously identified, structural vulnerabilities relating to some segments of the investment fund sector that I have previously outlined.

Developing and operationalising a macroprudential framework for market-based finance

This brings me to a key area of policy focus over the coming years. Developing and operationalising the macroprudential framework for market-based finance.

First of all, why macroprudential?

In seeking to explain macroprudential regulation, Andrew Crockett previously made the useful analogy of the financial system as a portfolio of individual securities.17 The macroprudential perspective focuses on the performance of the portfolio as a whole (in this case the financial system). Whereas the microprudential perspective focuses on the individual constituent securities (in this case, individual financial institutions). The macroprudential lens, therefore, places particular emphasis on the likelihood of correlated behaviour by individual financial institutions and the impact of that on the economy when shocks hit. That correlated behaviour may be due to exposure to similar exogenous shocks, similarities in underlying vulnerabilities driving common behaviour in times of stress or externalities from the behaviour of individual institutions, leading to endogenous common shocks.

I do not quote Andrew Crockett by accident. He was one of the thought leaders behind the introduction of macroprudential policy in the banking sector. The parallels today for the market-based finance sector are, in my opinion, clear. Back in 2009, Charles Wyplosz,18 summarising a report on the future of financial regulation, pointed out that, for banks, focusing on individual institutions represents a ‘fallacy of composition’, as homogenous action can collectively undermine the system.

“In trying to make themselves safer, banks, and other highly leveraged financial intermediaries, can behave in a way that collectively undermines the system. Selling an asset when the price of risk increases, is a prudent response from the perspective of an individual bank. But if many banks act in this way, the asset price will collapse, forcing institutions to take yet further steps to rectify the situation. It is, in part, the responses of the banks themselves to such pressures that leads to generalised declines in asset prices, and enhanced correlations and volatility in asset markets.”

Now consider if the word ‘bank’ is replaced with the word ‘fund’. The potential for collective action problems is, at heart, the main rationale for a macroprudential perspective in the market-based finance sector.

At the Central Bank of Ireland, we have been working with international counterparts, including at fora such as the FSB, ESRB, ESMA and IOSCO to not only ensure a coordinated international response to the recent COVID-19 shock to market functioning, but also on how to build resilience in this part of the financial system over the medium-term.19 Given the cross-border and interconnected nature of this form of financing, international cooperation is a key element of our work to fully understand the nature of the risks from a macroprudential perspective.

While some progress has been made in this area in recent years, the macroprudential framework for market-based finance is currently incomplete and not operational. Indeed, compared to the banking sector where the tools are already in place, macroprudential policy for the market-based finance sector remains at an early stage of development.

So what are some of the key priority areas for the macroprudential policy framework for market-based finance? I am not offering the answers today but I do want to outline some of the key questions that we will need to consider carefully (Slide 9: Developing the macroprudential policy framework).

First, what is the appropriate toolkit to target excessive liquidity mismatches and excessive leverage in the market-based finance sector? The business models of non-bank financial institutions, including investment funds, are very different to those of banks, as are the underlying channels through which they can amplify shocks to the economy and financial system. So we cannot just take what we have developed for banks and apply it elsewhere.

Work has started at an EU level to develop a framework for the imposition of ex-ante macroprudential leverage limits for funds.20 This tool can be used to build resilience by limiting the excessive use of leverage by funds. However, such leverage limits are partial in scope since they do not cover the entire funds sector and have not been operationalised. And as for liquidity mismatches, an important part of the toolkit – recognised by the ESRB and others – is to ensure the availability and timely use of liquidity management tools across the EU, especially in times of stressed market conditions.21 Still, there remains a question over whether the use of such tools by individual funds themselves would be sufficient from a system-wide perspective in times of stress.

Second, what is the appropriate balance between time-varying and structural interventions? For example, a closer alignment between funds’ redemption profiles with the liquidity of their underlying assets may address structural liquidity mismatches. At the same time, we know that the pricing of market liquidity risk by financial market participants is time-varying, which may also speak to exploring the possibility of time-varying interventions.

Third, what is the most appropriate approach to international co-ordination in this area? Capital markets are very international in their nature and gaps in coverage and co-ordination would limit the effectiveness of macroprudential policy interventions. Moreover, the actions by one jurisdiction can have a direct impact on financing conditions of another jurisdiction. So international co-ordination matters.

Fourth, how do we consider the appropriate balance between costs and benefits of additional resilience in the market-based sector? The global regulatory reforms to the banking system after the financial crisis involved a detailed cost-benefit analysis co-ordinated by the FSB and the BCBS. And macroprudential actions taken by individual jurisdictions always seek to balance the costs and benefits to the economy. This framework will need to expand to the market-based finance sector.

Conclusion

Let me conclude. I have heard it said that as the funds sector survived the COVID-19 shock, there is no need for a macroprudential framework for market-based finance. If you are in that camp, then I am afraid that you are either asking the wrong questions or have arrived at answers to a different set of questions. In my view the question isn’t “didn’t we do well?”, nor is it “what would have happened without central bank intervention on the scale that we saw in March?”, although you might guess what my response to that one is.

The question we need to address is: would a macroprudential framework for the market-based finance sector be good for the sector as a whole as well as for the stability of the financial system and ultimately the real economy?

For me the answer is clear and we should get on and address the gaps in the current framework for market-based finance so as to make it fully operational. Of course, there is no established playbook to guide us and there is limited experience with using such tools in this part of the financial system. But we faced similar challenges when developing and operationalising tools for the banking sector. And, together with our international colleagues, we are committed to taking forward this important work and developing and operationalising a more comprehensive macroprudential framework to safeguard financial stability.

__________________

1 Often referred to as non-bank financial intermediation, market-based finance can be defined as the raising of equity or debt through financial markets, rather than through the banking system.

2 European Central Bank: Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area (2020).

3 For example: Cima, Simone, Neill Killeen and Vasileios Madouros: ‘Mapping Market-Based Finance in Ireland‘, Central Bank of Ireland Financial Stability Note, Vol. 2019, No. 17 (2019); Lane, Philip R. and Kitty Moloney: Market-based finance: Ireland as a host for international financial intermediation, Banque de France Financial Stability Review, Issue 22, 63-72 (2018); Metadjer, Naoise and Kitty Moloney: ‘Liquidity analysis of Bond and Money Market Funds’, Central Bank of Ireland Economic Letter, Vol. No. 17 (2017); Lane, Philip R.: ‘Address by Governor Philip R. Lane to the International Capital Market Association Conference‘, (19 May 2016); and Godfrey, Brian, Neill Killeen and Kitty Moloney: ‘Data Gaps and Shadow Banking: Profiling Special Purpose Vehicles’ Activities in Ireland’, Central Bank of Ireland Quarterly Bulletin, Vol. No. 3, 48-60 (2015).

4 Cima, Simone, Neill Killeen and Vasileios Madouros: ‘Mapping Market-Based Finance in Ireland‘, Central Bank of Ireland Financial Stability Note, Vol. No. 17 (2019).

5 Allard, Julien and Roolphe Balvy: ‘Market Phoenixes and Banking Ducks Are Recoveries Faster in Market-Based Financial Systems?‘, IMF Working Paper, No. 11/213 (2011).

6 In addition to examining the different sources of finance, it is also important to consider the nature and risk profile of the financing being provided. For example, equity based finance has different characteristics to debt based financing.

7 For more detail, see my recent blog entitled “COVID-19 and Developments in Credit” which discusses some of these differences in financing channels in the euro area and US.

8 Financial Stability Board (FSB): Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Asset Management Activities (2017); European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB): Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 7 December 2017 on liquidity and leverage risks in investment funds (ESRB/2017/6) (2017); and International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO): Recommendations for a Framework Assessing Leverage in Investment Funds (2019).

10 Central Bank of Ireland: Financial Stability Review 2020: I: Box 6 Irish-resident funds and the market disruption at the onset of COVID-19 (June 2020).

12 See ECB: Financial Stability Review (2020).

13 Ibid.

14 de Guindos, Luis: ‘Financial stability and the pandemic crisis‘, remarks at the Frankfurt Finance Summit (22 June 2020).

15 Eren, Egemen, Andreas Schrimpf and Vladyslav Sushko: ‘US dollar funding markets during the Covid-19 crisis – the money market fund turmoil‘, BIS Bulletin, No. 14 (2020).

16 Schrimpf, Andreas, Hyun Song Shin and Vladyslav Sushko: ‘Leverage and margin spirals in fixed income markets during the Covid-19 crisis‘, BIS Bulletin, No. 2 (2020).

17 Crockett, Andrew: ‘Marrying the micro- and macro-prudential dimensions of financial stability‘, remarks before the Eleventh International Conference of Banking Supervisors, Basel (20-21 September 2000).

18 Wyplosz, Charles: ‘The ICMB-CEPR Geneva Report: The Future of Financial Regulation‘, VoxEU (27 January 2009). The column summarises the report written by Brunnermeier, Markus, Andrew Crocket, Charles Goodhart, Avinash D. Persaud and Hyun Shin: The Fundamental Principles of Financial Regulation, IMCB-CEPR Geneva Reports on the World Economy 11 (2009).

19 ESRB: Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 6 May 2020 on liquidity risks in investment funds (ESRB/2020/4) (2020).

20 ESRB: Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 7 December 2017 on liquidity and leverage risks in investment funds (ESRB/2017/6) (2017).

21 ESRB: Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 7 December 2017 on liquidity and leverage risks in investment funds (ESRB/2017/6) (2017), and ESRB: Use of liquidity management tools by investment funds with exposures to less liquid assets (2020).